We believe your behaviour will likely have a bigger impact on your returns than we will as the managers of your money.

We also believe behaviour is hard to teach. We think about how hard it is to change for the better. We may have the best intentions to do so, but often fail in modifying our behaviour to achieve the desired outcome. If we can’t even change ourselves as often as we’d like, why do we think we’ll be able to change others?

Maybe we’re fools for trying, but this commentary is dedicated to modifying how you behave in the future with your Cymbria investment. We believe that behaving a certain way with your investment will increase your probability of a positive experience.

Nobel laureates have written textbook after textbook on behavioural finance. These very smart people have dissected the human condition in excruciating detail. We’re not Nobel laureates and we don’t think you want to read a finance textbook. Therefore, this commentary will focus on helping you understand only two behavioural elements:

We believe returns will be lower and volatility higher in the future and that you should behave accordingly with your Cymbria investment.

That anything worthwhile usually takes time to accomplish and building wealth with Cymbria isn’t any different.

The future will be different from the past

A hallmark of some profitable investments is that they start with discomfort. A little under a decade ago, investing in Cymbria was uncomfortable. When we started in 2008 many wondered whether the world would ever recover from the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. In the midst of this crisis, a brand-new investment organization called Cymbria was asking investors for their trust. Those who believed that the economy would recover and that Cymbria would be a pleasing fiduciary of their capital benefited.

It’s not nearly as uncomfortable to be invested today. As such, our view of the next decade is that it won’t be as rosy as the last from a returns perspective.

Entry price dictates returns. For our first eight years, we were the beneficiaries of regular controversy (a.k.a., fear) in the marketplace that created attractive entry prices for us, and by default for you as our investor. Events including the global financial crisis, Greece, the U.S. debt downgrade and the emerging markets slowdown triggered healthy bouts of market volatility. This volatility in turn created fear which caused stock prices to fall which provided attractive entry points for us to take advantage of on your behalf.

We’ve seen much less volatility lately.

We’re in the second-longest bull market since World War II, at 111 months and counting. Since 1990, the S&P 500 Index’s average intra-year decline has been -13%i. However, the last time the S&P 500 dropped by at least this amount intra year was in 2011ii. All of this enthusiasm has resulted in a lack of fear and in turn a lack of downside volatility in stock prices.

Investors may understand that the higher the entry price, the lower the prospective return. They may also understand that volatility is the only constant in the stock market. Unfortunately, in spite of understanding these ideas, investors are prone to conduct their affairs as though they don’t. There are many behavioural reasons for this, but we believe a major contributor is that emotions are contagious. When others feel optimistic or excited about something, it’s easy to be influenced by them. Here’s an experiment you can do to prove this point to yourself.

Fill a glass with 150 jelly beans. Pass the glass around and ask people to guess how many jelly beans are in it. Let them take as much time as they need to come up with a number then get them to write it on a piece of paper and not show anyone.

At this point ask the participants to each say their number one at a time. The catch, however, is that your accomplice goes first. The accomplice is someone who you’ve previously arranged to guess out loud that the glass contains 400 jelly beans.

What do you think happens? We’ll wager that almost everyone will say a higher number out loud than what they wrote down. What’s more, their original guess will be within 20% or so of the correct number.

To achieve the best investment outcome, you must shut out the noise and focus on the facts. It’s a bit ironic that the average investor uses social proof generated from short-term thinking to guide their investment decisions when investing success usually stems from a long-term view based on contrarian thinking. It’s easy to let the noise distract you from what you know and this can be dangerous to your financial health.

The chart below shows the S&P 500 Index’s subsequent 10-year compound annual return resulting from different price-to-earnings (P/E) valuations. The point is to show that future returns are inversely correlated to valuations.

Source: “U.S. Stock Price Data, Annual, with consumption, both short and long rates, and present value calculations”, R. Shiller, http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/chapt26.xlsx. Current P/E ratio as at June 30, 2018. All data is at the listed year’s last calendar date and in US$. Returns are total returns. Earnings are the reported, unadjusted numbers. The S&P 500 Index is a broad-based market-capitalization-weighted index of 500 of the largest and most widely held U.S. stocks. Shiller-sourced P/E ratio: The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 Index compiled by Robert J. Shiller. This is different from the Shiller P/E which is a price-to-earnings ratio adjusted for cycles and inflation. Line of best fit: The scatter chart’s solid line represents the weighted average of the points to show a general trend. The line’s downward slope (going from left to right) means that as the Shiller-sourced P/E ratio goes up (moves to the right), S&P 500 returns for the subsequent 10-year period go down.

For example, in 1980 investors were fearful as the economy went into recession and interest rates rose. As a result, P/E ratios were relatively low at 7.5x and the Index’s ensuing 10-year annualized return was relatively high (at 17.5%).

Conversely, around the height of the dot-com bubble in the year 2000 when greed dominated the market, the P/E ratio was relatively high at 29.6x whereas the Index’s subsequent 10-year annualized return plummeted to -1%.

What’s clear is that the higher the entry price, the lower the eventual return.

Following is a chart showing the S&P 500’s average intra-year declines over the last 38 years, something I referenced earlier. The average intra-year drop is 13%. For the last 6.5 years, we haven’t even hit the average. Actually, 7.5 of the last 8.5 years have been above average as well.

Source: Bloomberg LP. As at June 30, 2018. Returns based on price index only, excludes dividends and in C$.

Maximum decline is the largest intra-year market drop from a peak-to-trough during the calendar year. Calendar-year returns shown from 1980 to 2017. Maximum decline and return for 2018 are as at June 30, 2018 and do not represent a full calendar year. The S&P 500 Index is a broad-based market-capitalization-weighted index of 500 of the largest and most widely held U.S. stocks.

Forget that investors seem to be comfortable investing in the stock market today. Forget how much money has been made in the past decade or how smooth the ride has been most recently. Forget the enthusiasm around Cymbria’s historical performance. You know how many jelly beans are in the jar. You understand that the higher the valuation when you invest, the lower the prospective returns. You also understand that volatility has been below average recently, and that the market is likely going to see declines in the future greater than what has happened in the recent past. In the future you’ll need to act on your understanding.

You shouldn’t invest with Cymbria today if you expect our future returns to be anything like our historical ones. You shouldn’t invest with us if you think our future volatility will be as muted as in the past. In fact, please don’t give us any money today unless you’re willing to invest more when the market is down -20%. If you can’t do that, don’t invest with us. We’ll disappoint you if you do.

The best edge to exploit is long-term thinking

Our primary goal is to deliver performance at or near the top of our peer group over a 10-year timeframe. A derivative of this goal is making sure that our investors achieve the same returns as our Portfolios, something we don’t see happening a lot in our industry. More common is for investors to buy a fund when its historical numbers look good and sell when its historical numbers look bad. The end result is that investors tend to do worse than the fund itselfiii.

Let’s give you a real-life example. Joel Greenblatt is a famous investor and author of The Big Secret for The Small Investor. In it he recounts how the stock market was essentially flat during the decade from 2000 to 2010 yet the best-performing mutual fund returned 18% per yeariv. Pretty good! How did its investors do? The answer is they lost -11% a year on a money-weighted basis. How do you lose -11% annually in an investment that compounds at 18% annually over 10 years? It’s easy – buy it when it’s doing well and sell it when it’s doing poorly.

As Cymbria is a publicly listed company, we can't know who buys it and their investing patterns. While there's a lack of insight on our shareholders' investment behaviour, we closely analyze the end-client activity of our four EdgePoint Portfolios.

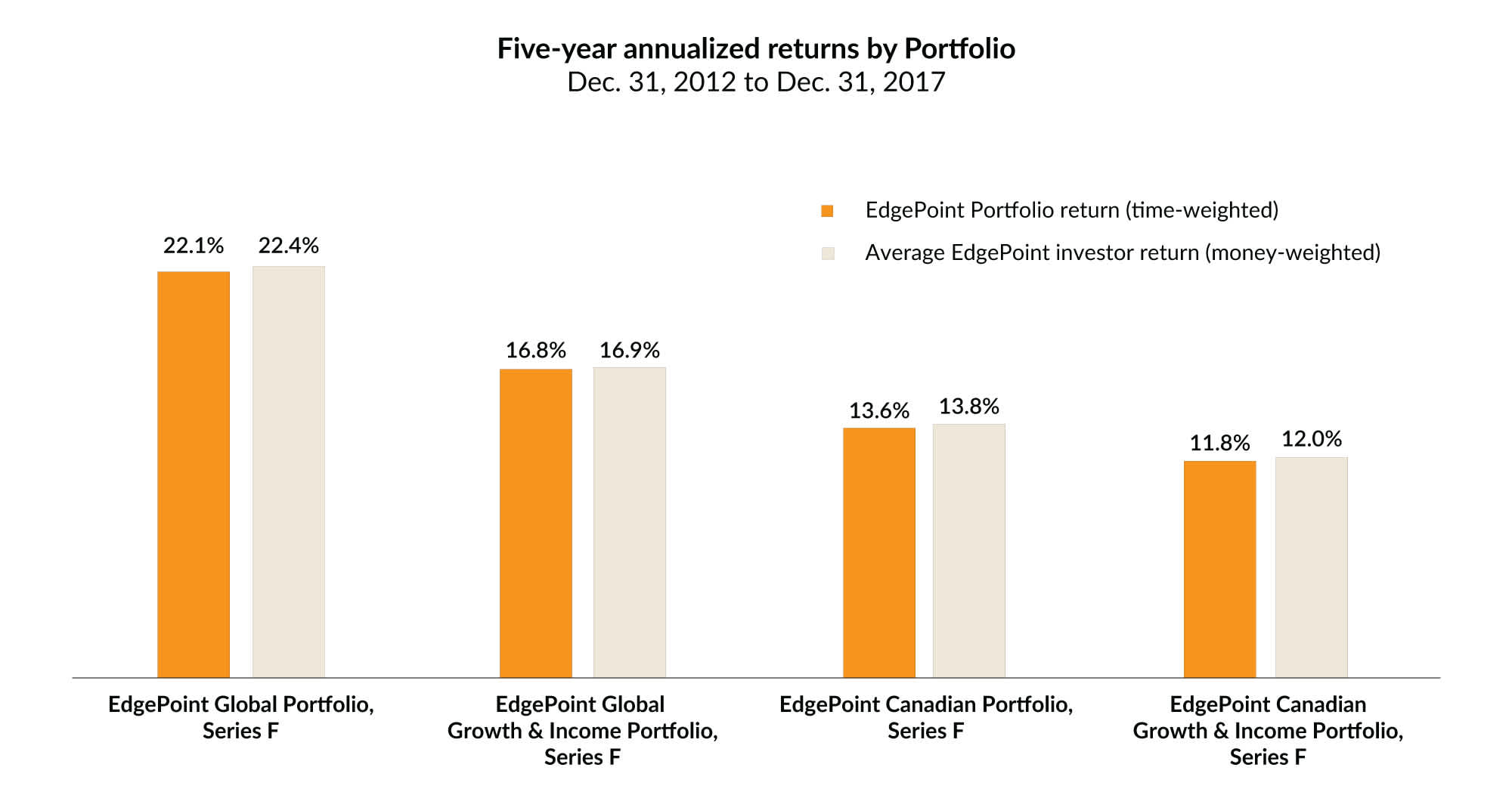

Here’s how our EdgePoint investors have performed over the past five years compared to our Portfolios:

Portfolio performance as at December 31, 2017. Annualized total returns in C$, net of fees.

EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series F: YTD: 18.01%; 1-year: 18.01%; 3-year: 15.54%; 5-year: 22.05%; since inception: 18.74%; EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio, Series F: YTD: 10.79%; 1-year: 10.79%; 3-year: 10.26%; 5-year: 13.63%: since inception: 15.27%; EdgePoint Global Growth & Income Portfolio, Series F: YTD: 13.38%; 1-year: 13.38%; 3-year: 12.14%; 5-year: 16.83%; since inception: 15.18%; EdgePoint Canadian Growth & Income Portfolio, Series F: YTD: 9.32%; 1-year: 9.32%; 3-year: 8.90%; 5-year: 11.84%: since inception: 13.07%

As at December 31, 2017. Source, EdgePoint Portfolio returns: Fundata Canada, net of fees. All returns annualized and in C$. Source, average EdgePoint investor returns: CIBC Mellon. Average EdgePoint investor returns are the average money-weighted returns net of fees across investors who held EdgePoint Portfolios, Series F from December 31, 2012 to December 31, 2017. EdgePoint Portfolio returns are time-weighted to best reflect the manager’s performance based on compound growth rate, which isn’t impacted by portfolio cash flows. Money-weighted average investor return takes into account the investor’s decision(s) regarding the timing and magnitude of cash flows and represents their personal rate of return. Series F available to investors in fee-based/advisory fee arrangement and excludes trailing commissions.

As you can see, as a group they’ve achieved results commensurate with our Portfolios. We believe this reflects the quality of our investors and their advisors. If you’ve been with us longer than three years, you and your advisor likely understand what you own and had conviction to stay the course when the market declined or when we looked dumb relative to the market. In fact, many of you added to your positions during these rough patches, improving your eventual outcome.

We want this trend of investors achieving close to the same returns as their EdgePoint Portfolio to continue.

To do so you must understand that we will look completely dumb at some point. Perhaps we’ll decline more than the market when it goes down or maybe we won’t go up as much when the market increases. Attempting to outperform over the long term means looking different from the market. Sometimes we’ll zig when the market zags and this will feel uncomfortable.

Let’s quantify how uncomfortable.

Greenblatt also analyzed the top quartile of managers over the 2000 to 2010 period, those who had beat 75% of their peers, and showed that:

97% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three of those years in the bottom half of performance

79% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three of those years in the bottom quartile (bottom 25%) of performance

47% of managers with the best 10-year record spent at least three of those years in the bottom decile (the bottom 10%) of performance

Here’s why we believe most investors underperform. First, it’s hard to find active managers who can actually beat the market. Then, even if you happen to find one, it’s hard to stick with them when they look wrong.

How much time have EdgePoint Portfolios spent looking wrong since we started? Let’s look at our Global Portfolio for the answer as it’s our biggest in terms of assets and investors. On a calendar-year basis, EdgePoint Global Portfolio has spent only two years in the bottom half of performance for its peer group, zero years in the bottom quartile and zero years in the bottom decilev.

The same stats for all of our Portfolios are as follows:

| Bottom half | Bottom Quartile | Bottom Decile |

|---|

Our history of almost no underperformance is an anomaly. Forecasting that anomalies will continue is unwise. Of course, we’ll try to outperform year in and year out, but you should expect that our historical path of relative historical returns is unlikely to be repeated. Spending so little time looking wrong over a decade just isn’t prudent to extrapolate into the future. In addition to the monetary impact of the fees you pay, you might consider the emotional strain of sticking with us through a prolonged bout of underperformance (three years, for example) as the additional cost of potentially achieving long-term financial rewards with our investment approach. This emotional fee may be very large in the future. What’s worse is that while you’re paying it, no one (including us) will be able to guarantee that you’ll see a sufficient payoff. Making money through investing can be brutally difficult sometimes. If it was easy the world would be rich, but as we know, it isn’t.

If you really can’t see yourself staying the course with your EdgePoint investment when it underperforms, then you’d likely be best served to sell it today. Our preference would be to keep our investors; however, we know this is unrealistic. A clever person once said that even God would lose clients as an active manager. So we’d rather those who are self-aware enough to know today that they won’t stick with us during a down period to sell their EdgePoint investment while we still have pleasing relative performance.

Compounding wealth takes patience and nerves. It requires an understanding and belief in the approach guiding your investments. You can review our investment approach here. Most of all for us, compounding wealth requires an unrelenting focus on the long term.

In conclusion

Cymbria risks being perceived as a sure thing. Our historical performance has led many stakeholders to believe that we’ve found a magic formula for success. There are few things more dangerous in the investment business. We don’t believe we’re a sure thing nor do we conduct ourselves as though we are.

We do believe in the strength of our investment approach and that it can help build your wealth over the long term.

Some of our investors shouldn’t be investing their hard-earned savings with us. The problem is we don’t know which ones. We’d reach out to them directly if we did know. Barring that, we recognize the importance of communicating the following message to everyone:

Future returns will be lower than past returns.

Future volatility will be higher than past volatility.

We won’t always look as smart as we do now.

While discomforting, this is the truth.

It’s why we believe your behaviour in the face of these truths will have a greater impact on your eventual returns than your portfolio’s underlying performance.

If you invested with us during times of uncertainty, we thank you for your trust and applaud your ability to manage your emotions. For those new to Cymbria, we encourage you to reflect on this note and how you might handle short-term underperformance.

We continue to approach investing in these markets with measured confidence, value your trust in us and look forward to working to build your wealth in an effort to be worthy of that trust.

ii Bloomberg LP.

iii Morningstar Inc. “Mind the Gap: Global investor returns show the costs of bad timing around the world” May 30, 2017.

iv Joel Greenblatt, The Big Secret for the Small Investor. Simon & Schuster Audio, 2011.

v Morningstar Inc. Quartiles divide data into four equal regions. Expressed in terms of rank (1, 2, 3 or 4), the quartile measure shows how well a mutual fund has performed compared to all other funds in its peer group. The top 25% of funds (or quarter) are in the first quartile, the next 25% of funds are in the second, and the next group is in the third quartile. The 25% of funds with the poorest performance are in the fourth quartile. Quartile rankings are subject to change every month. Peer groups for EdgePoint Portfolios are as follows: EdgePoint Global Growth & Income Portfolio – Global Equity Balanced; EdgePoint Global Portfolio – Global Equity; EdgePoint Canadian Growth & Income Portfolio – Canadian Equity Balanced; EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio – Canadian Equity. Series F is available to investors in a fee-based/advisory fee arrangement and excludes trailing commissions.

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 |

|---|