Over the holidays, I read a biography about John Wooden, the legendary college basketball coach. From 1963 to 1975, he won 10 national championships; a record unlikely to be broken. As a fan, I marvelled at his coaching success and wondered how he was able to find that “elusive edge.” Reading it, I expected to find accounts of sophisticated play designs or ahead-of-its-time analytics. Instead the book is filled with simple ideas. For example, at the beginning of the season the players arrived to practice expecting to run drills. To their surprise, Coach Wooden asked them to gather in a circle, sit down and take off their socks and shoes. As the players looked around in disbelief, Coach Wooden proceeded to explain the right way to put on their socks to avoid performance-hampering blisters. It’s a simple routine that any coach across the country could have done, but the idea probably never crossed their minds.

All winning organizations have an “unfair” advantage that others can’t copy. Often what makes them successful is deceptively simple – easy to understand but hard to replicate.

In this commentary, I want to discuss one deceptively simple idea. Why time, specifically using more of it, is the most powerful advantage an investor can have.

Blinking contest

There’s an old saying that if you want to beat the market you can’t be the market. The only way to do better than everyone else is to be different. Blindly straying from the crowd probably means being worse, but having good reasons for being different creates an edge. We refer to this as having a proprietary insight, a view about a stock that isn’t widely shared by others.

Most investors focus on getting an information advantage which means finding data about a business others don’t have. The truth is it’s very difficult to have an informational edge. Our industry is filled with intelligent people analyzing the same company filings and attending the same conferences.

I believe the most overlooked edge an investor can have is time – the willingness to look further out than other people. Fortunately, those who want a time advantage don’t have to wait as long as they used to since investors are holding their stocks for shorter and shorter periods:

Average holding period for NYSE stocksii

| 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

|---|

In the 1980s and 90s, the average investor held a stock for two or three years. It was necessary to look out four or five years to have a variant view. Today, having a view about a business two or three years from now can be a proprietary insight.

You probably think this sounds silly. Why would anyone hold a business for seven months and expect a favourable result? Imagine if your neighbour asked for money to buy the local Tim Hortons franchise with the intention of flipping it in seven months. You’d politely say no. But this type of thing happens in the stock market every day.

If all it takes to beat the market is waiting a few extra years, why doesn’t everyone do this? It turns out that this simple idea is very difficult to do in practice.

Three’s company

I’m going to try to illustrate this with a thought experiment. Let’s say we wanted to start a new investment firm (we’ll call it Triple Threat Co.) that’s going to take advantage of other people’s short-term behaviour. I think we would all agree Triple Threat Co. would need three things to succeed:

People (employees)

Environment

Clients

The ideal people are long-term thinkers operating in an environment that discourages short-term behaviour working with a client base that thinks the same way. Unfortunately, it’s hard to find all three ingredients in the same place.

Let’s walk through the checklist of our ideal company.

1. People

The trouble with trying to hire long-term thinkers is that it’s not natural for people to think this way. Most of us are wired to be short-term thinkers.

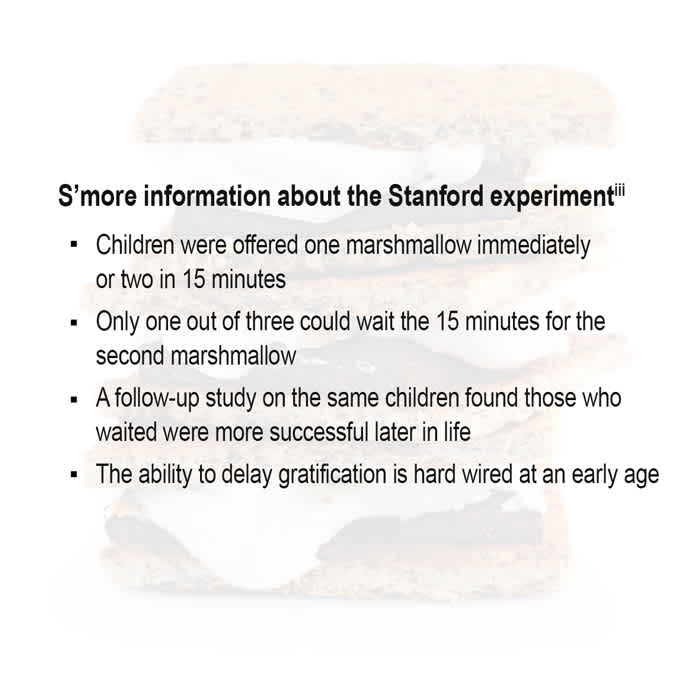

In the late 1960s, Stanford University researchers proved this by using marshmallows to show how bad people are at delaying gratification (a fancy term for long-term thinking).

The stock market is an adult version of the marshmallow experiment. When people invest, they’re choosing to give up consumption today in order to consume more in the future. Unlike the Stanford study, you don’t know how many marshmallows you’re going to receive or how long you have to wait. It’s the ultimate test of long-term thinking. A test most people are falling short on based on the average holding period.

The stock market is made up of people who resemble the kids in the marshmallow experiment. If you’re buying a stock from someone who has trouble delaying gratification, they’re going to undervalue the kinds of businesses that can grow – the ones we want.

2. Environment

Let’s assume we found enough people who are wired to think differently. The next step is designing the ideal structure. If we have the right people, does the environment really matter?

A recent study by the University of Rochester found that environment had just as much influence as “hard wiring.” The researchers found that if the children felt safe and comfortable, they were more likely to delay gratification (i.e. their performance improved).

How do you create a safe and trustworthy environment in the investment business? It’s easier to figure out what wouldn’t work. You probably wouldn’t tie employee compensation to quarterly or annual performance. You wouldn’t pressure the portfolio managers to own a business simply because it’s in the index and everyone else owns it. Nobody would be forced to sell a stock because the share price fell shortly after buying it.

It sounds simple, but why are these common practices in the industry?

3. Clients

At this point, we’ve found the right people and thought about the right environment. The last step is partnering with the right clients. Even if Triple Threat Co. gets the first two things right it won’t be enough. The only way to be successful is to have all three.

I was recently at a conference in New York and met with an analyst at a reputable hedge fund. We happened to be looking at investing in the same business. We had a long conversation and I was impressed with the depth of his research and insights into the business. At the end of the conversation I asked, “What happens if you’re wrong?” After a long pause he told me that if anyone on his team experiences a loss of more than 10% they’ll be out of a job. No exceptions.

On my way home I reflected on this conversation. Why would savvy investors structure their organization this way? I think the problem stems from them attracting the wrong clients. The investment firm created an environment that catered to the clients’ wants (short-term gratification) but not their needs (helping them get from Point A to Point B). There are dozens of successful hedge funds located within a couple of blocks and clients know if their fund manager underperforms, other options are a building (or even a few floors) away. A short-term oriented client isn’t going to stick with a manager who is down 10% when there’s another manager who might be having a good year just around the corner.

Investing isn’t just luck

Cymbria is very fortunate to have found an investor base of like-minded people. During periods of heightened volatility our partners not only stayed the course but many invested more money.

Our all-star advisors (you) are one of our most important assets. You allow us to focus on making the investment that’s right for your clients, instead of the one that makes them feel good right now.

One example is how you react to volatility. Many people in our industry view volatility as risk. Understandably, there are few things more uncomfortable than watching your life savings temporarily go down in value. Some investors are so afraid of volatility they build a portfolio to minimize these painful swings.

You view volatility the same way we do – it’s the friend of the investor who knows the value of a business and the enemy of the investor who doesn’t. Markets have been and always will be volatile. It’s our job to know the value of businesses so that we can take advantage of volatility (i.e. buy businesses from people who are panicking) to your benefit.

This is a list of stocks since inception in Cymbria that have gone down at least 10% after we bought them.

| Holding | Drawdown | Holding Period Return | Holding | Drawdown | Holding Period Return |

|---|

Source: Bloomberg LP. The above includes names that returned at least 10% over their holding period and had at least a 10% drawdown. Drawdowns in local currency, price returns. Holding-period returns in C$, total returns.

Fifty-seven times we bought a business thinking we had a proprietary insight only to watch it drop 10%, 20%, sometimes even 60% during our holding period. Unfortunately, volatility doesn’t go away after we buy a business. It also means that if we had a similar structure to the hedge fund we would’ve been fired 57 times!

During many of these downturns, we committed more of your capital to these names as they went down. The result is that you experienced a higher return on your investment than if the stock went straight up after our purchase.

Let’s use a recent example to illustrate how time worked to our advantage. In June 2015, we purchased Ubiquiti Networks, Inc. in Cymbria with an idea of how the business could be much bigger in the future.

Ubiquiti Networks, Inc.

Source: Bloomberg LP. June 1, 2015 to December 31, 2016. In US$.

In the short term, investors worried about a slowdown in Ubiquiti’s end markets and the stock dropped by 19.31%. We looked at the same business and saw the long-term growth potential was still intact. Our thesis gave us the comfort to significantly increase our position and, eventually, our returns.

History has shown that our investment approach is best suited to periods of uncertainty. The greater the price fluctuations, the greater our ability to add value. We can’t take advantage of these movements if we’re forced to sell too early. Without your trust, none of this is possible.

We’re constantly working on getting the right people, environment and clients and are pleased with our start thus far.

ii Warren Fiske, “Mark Warner says average holding time for stocks has fallen to four months”, Politifact Virginia, July 6th, 2016, http://www.politifact.com/virginia/statements/2016/jul/06/mark-warner/mark-warner-says-average-holding-time-stocks-has-f/.

iii W. Mischel, E.B. Ebbesen and A.R. Zeiss, “Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay gratification,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, v.21(2) February 1972: 204-18.

ivCeleste Kidd, Holly Palmeri and Richard N. Aslin, “Rational snacking: Young children’s decision-making on the marshmallow task is moderated by beliefs about environmental reliability,” Cognition, v.126(1), January 2013: 109-144.