Where has the time gone? – 3rd quarter, 2021

Since this is my first commentary for Cymbria I was having some writer’s block trying to decide on a relevant topic that would also interest you. I’ve always thought that success in investing requires many attributes: ability to value what a business is worth, discipline to keep your emotions in-check while sticking with your strategy, and having a longer-term time horizon. Previous Cymbria commentaries have covered valuation and staying within a narrow emotional band, so I’m going to elaborate more on how increasingly shorter time horizons are detrimental to an investor’s investment returns and the important goal of reaching their Point B.

Ben Graham was an influential investor whose writings laid the foundation for fundamental in-depth research on stocks. He wrote that in the short run the market is a voting machine, but in the long run it’s a weighing machine. He meant that anything could happen to stock prices in the short term. Even when a business is growing revenues and earnings, its stock price can still decline for reasons completely independent. Over the long term, if good things are happening in the business, then eventually these positive factors will also be reflected in the stock price. However, this approach requires patience. The shorter your time horizon, the greater the likelihood that chance may come into play regarding your returns.

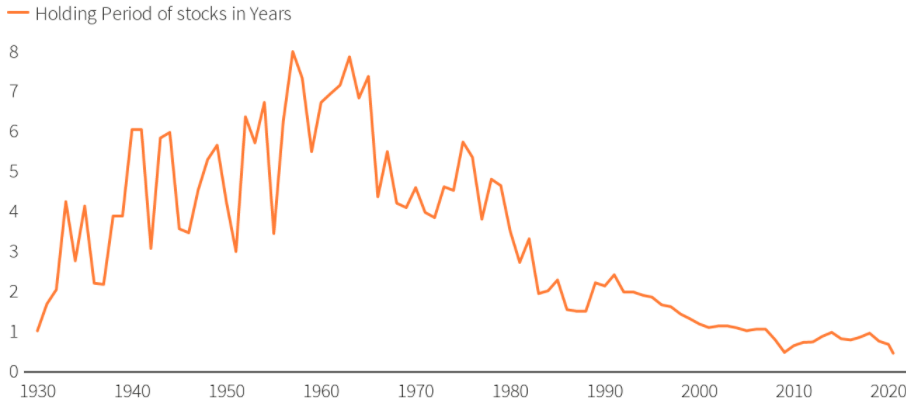

While society continues to make advancements in many areas, one area that’s going backwards is people’s attention span. In financial markets, the average holding period for U.S. stocks by retail investors has declined from eight years in the 1960s to less than 5 months as at August 2020.i Although we know that having a long time horizon is extremely important for long-term success, the average holding period for investors has shrunk by 95%! Most self-made fortunes are largely the result of owning and growing a business over years, possibly even decades, but surely not mere months. Stocks represent ownership interest in a business, not just pieces of paper to speculate on in the marketplace.

Holding period of U.S. stocks

1930 to 2020

Sources: Saikat Chatterjee & Thyagaraju Adinarayan, “Buy, sell, repeat! No room for 'hold' in whipsawing markets”, Reuters.com, Aug. 3, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-short-termism-anal-idUSKBN24Z0XZ, NYSE, Refinitiv. Holding periods measured by the value of stocks divided by turnover.

Are professional investors any better?

Even though they’re highly skilled with advanced education and often CFA designations, most professional investors still underperform the index. Why? They’re also impacted by short investment time horizons. On average, the clients who invest with these managers only stick around for a couple of years, so fund managers are under immense pressure to produce immediate returns. If they don’t, then clients may leave, and if that happens too often, the manager may lose their job.

This impatience also works against unitholders as they have a tendency to let emotions sway their investment decisions. Many will buy after recent periods of strong returns and sell when returns are weak – by buying high and selling low, they’re doing the opposite of what they should. Research done by Dalbar Inc. shows that for the 20 years ending December 31, 2020, the market returned on average 7.47% while the average equity fund investor earned a return of only 5.96%;ii approximately 20% lower on an annual basis. Compounding $100,000 over an average investor’s timespan of 40 years, the average unitholder would have grown their wealth to $1.01 million compared to $1.78 million for the underlying fund, or 43% less.

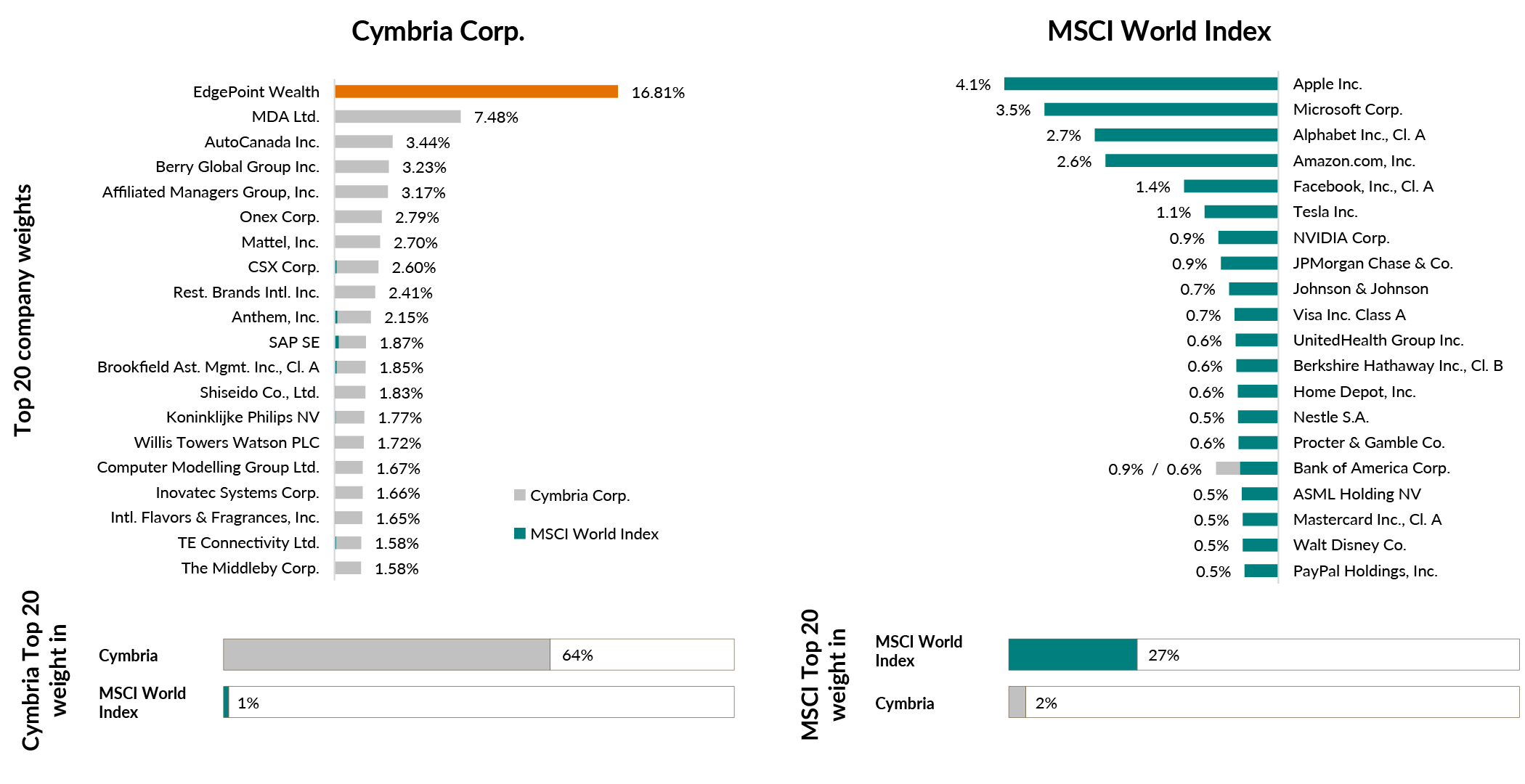

This short-termism creates two results among professional fund managers: closet indexing and excess portfolio turnover – which both work against the best interests of investors. Closet indexing occurs when professional investors clone their portfolios to basically match the index, all in the name of not underperforming. The problem is you can’t outperform when you own essentially the same stocks as the index, and you’re almost guaranteed to underperform when you factor in the higher fees and expenses that active managers charge. As John Templeton said, “if you want to have better performance than the crowd, you must do things differently from the crowd.” The table below shows the difference in holdings between the EdgePoint Global Portfolio and the MSCI World Index.

Cymbria vs. MSCI World Index top-20 company weights

As at September 30, 2021

Source: FactSet Research Systems Inc. As at September 30, 2021. The MSCI World Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index comprising equity securities available in developed markets globally. We manage our Portfolios independently of the indexes we use as long-term performance comparisons. Differences including security holdings and geographic allocations may impact comparability and could result in periods when our performance differs materially from the index.

When portfolio managers are under pressure to always perform well, they tend to constantly trade, which incurs high expenses. A study shows the average mutual fund had an annual turnover ratio of about 89%,iii meaning the typical fund buys and sells nearly its entire asset base every year. The more decisions you make, the greater the chance that you make a mistake. How much deep fundamental research is being done on these ideas? It’s not uncommon for Cymbria investment professionals to spend over a month researching a single idea. Given that we are investing people’s life savings, extreme care and diligence is required.

There is also an undue focus on the very short term (e.g., the next couple of quarters). When researching new ideas, we’ll sometimes hear, “it’s a good business but there are no near-term catalysts, it’s dead money for the next six months, and look at it later.” By the time consensus starts to reflect positive news, it’s usually too late and the stock price has moved higher. With so many people focused on the short term, to outperform you need to do something differently and, for us, that can be the willingness to look further out.

We’re willing to long wrong in the short term to be right in the long term.

Mark Twain once said, “history never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” Investors as a group tend to ignore the lessons of history. They buy what’s recently been “working” in the stock market, regardless of valuation. Indeed, there’s always comfort in being part of the herd and not taking the risk of standing out from the crowd. Like the old quote said, “nobody gets fired for buying IBM.” The implication is that IBM was the “safe option.” If you invest in widely held names that underperform, there’s safety in numbers of many others also owning them. There’s a reluctance to invest in non-consensus names because of the fear of being alone and being wrong. The next table shows that the biggest and most widely held names rarely repeat from one decade to the next – winners one decade tend to underperform the next. The crowd has done a 180-degree turn in the last decade by switching from commodities to technology – they did the opposite in the previous decade (sold technology and bought oil). This short-term pressure to always invest like everyone else, regardless of valuation bubbles, has usually been dangerous to your wealth. It’s like picking up nickels in front of a steam roller – eventually you’re not fast enough and you get squashed.

Top-10 companies in the world by market cap

1980 to Sep. 30, 2021

Source, decades: J. Mauldin, “Bonfire of the Absurdities”, Mauldin Economics, November 17, 2017, http://www.mauldineconomics.com/frontlinethoughts/bonfire-of-the-absurdities/. Source, September 30, 2021: FactSet Research Systems Inc. Market cap in US$.

The perils of short-term focus

Frequent turnover and short-term focus lead to over-diversification and not having conviction in your holdings. When prices go down, people tend to panic – what should they do next? Would you be surprised that roughly half of all managers don’t even invest in their own funds?iv I wonder if their clients know?

Executives working in the investment management industry should have the best appreciation that investment success requires a long-term time horizon, but unfortunately, they’re usually no better. A survey from a few years ago showed that 89%v of asset management executives would NOT tolerate two years of underperformance and would make a change in manager (probably at the wrong time, too). Is this myopic stance a by-product of more investment firms now being run by sales and marketing people instead of actual investors?

The table below shows the track records of various outstanding investors, such as Warren Buffett and John Templeton. Even though they outperformed over the long term, on average they underperformed the index in any given year about one-third of the time. Their lifetime success clearly demonstrates that they ignored the short-term noise and focused on the long-term fundamentals.

Top investment managers

Years active, % of years underperforming the S&P 500 Index and annualized outperformance vs. the S&P 500 Index

Source: Tweedy Browne Co., “10 Ways To Beat An Index”, 1998; Warren Buffett, “The super investors of Graham-and-Doddsville”, Hermes, Fall 1984; and V. Eugene Shahan, “Are short-term underperformance and value investing mutually exclusive?”, Hermes, Spring 1986. Total returns in US$. Buffet’s investment return is based on the change in per-share market value of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s Class A shares. The S&P 500 Index is a broad-based, market-capitalization-weighted index of 500 of the largest and most widely held U.S. stocks.

The sell side employs armies of research analysts to study companies and recommend investment ideas to their buy-side clients. Many of these people have decades of experience covering their sectors and have gained considerable knowledge. Given the shortened time horizons of buy-side clients, more attention is now devoted to shorter-term trivial issues that don’t matter in the long run, with less time spent conducting comprehensive, fundamental research. Conference calls have devolved into what’s happening next quarter instead of digging into long-term strategic issues of where the business is going. Many times, these “issues du jour” being asked about today will be forgotten next year, but still create churn in client portfolios.

A recent internal research project involved interviewing the top 11 customers of a company’s products, with the goal of developing an in-depth proprietary insight. Our longer-term focus allows us to look in all the “nooks and crannies” of a company and know it much better than our peers, which gives us an advantage. While competitors are usually focused on the next couple of quarters, we’re focused on the next three to five years.

Closing the circle, companies are also affected by this sea of short-termism that surrounds them. High turnover among shareholders requires management teams to take time away from their primary responsibility of running their business. Instead, they always seem to be educating a revolving base of new shareholders. Some CEOs spend more than a quarter of their time on this unproductive activity.vi Instead of investing to maximize long-term value creation, some management teams fear that doing so will penalize short-term profits and displease investors – the same group that’s here today and gone tomorrow. In good times, shareholders push for share repurchases when stock prices are also high, as that helps their own short-term performance. When times are bad, managements are pushed to cut costs, de-lever and forego strategic investments, all in an effort to shore up short-term earnings and stock prices. CEOs have publicly declared that an advantage of going private (i.e., no longer being publicly traded on the stock market) is not having to deal with short-minded shareholders. More egregious cases involve companies using aggressive accounting or even outright fraud in order to make next quarter’s “street numbers.”

Given the constantly changing shareholder base of the largest public companies, it’s perhaps not surprising that we often witness large swings between their 52-week high and low stock prices. The table below shows the percent spread between calendar-year high and low stock prices for the 10 largest companies in the MSCI World Index, averaged over last five- and 10-year periods ending in 2019. We’ve excluded 2020 data owing to the pandemic’s impact on markets, or these numbers would be even greater. For example, Apple has averaged a 60% difference between its annual high and low share price over the last five years. These are some of the biggest market capitalization companies in the world, have stable earnings power and are widely held by investors, yet we see large differences between calendar-year high and low stock prices that persist over long time periods.

| Holding | 5-YEAR AVERAGE (2015 TO 2019) | 10-YEAR AVERAGE (2010 TO 2019) |

|---|

Source: FactSet Research Systems Inc. Top-10 largest MSCI World Index companies as at September 30, 2021.

Many of the above are technology companies, but looking at the wider universe of the S&P 500 Index, the median spread of any given stock between annual high and low stock prices has averaged 35% over the last five years.vii Sometimes these price moves have nothing to do with the underlying business. Underlying changes in intrinsic value are more gradual than what’s seen in the stock market and can benefit patient long-term investors like Cymbria.

How is Cymbria different?

We’re a firm founded and run by investors

Investment success requires a long-term focus, and our holding period is measured in years rather than months

We try to look further out and develop a proprietary view around our holdings that gives us conviction in our holdings

Investment professionals must own multiples of their salary in our Funds. vii Collectively, internal employees have more than $352 million of our own savings invested alongside you in our Funds, including Cymbria. ix

Focusing on EdgePoint, the largest holding in Cymbria – Our partnership with like-minded advisors has resulted in our clients having long holding periods, and our average unitholder return has been very close to the returns of the Funds themselves as a result. On average, unit holders in EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series F experienced a 10-year return of 15.6% and slightly outperformed the Portfolio which returned 15.0x

Cymbria Corp., Class A NAV vs. MSCI World Index Growth of $20,000

Nov. 3, 2008 to Sep. 30, 2021

Performance as at September 30, 2021. Annualized, total returns, net of fees, in C$

Cymbria Corp: YTD: 12.63%; 1-year: 31.11%; 3-year: -0.15%; 5-year: 11.17%; 10-year: 17.80%; Since inception (Nov. 3, 2008): 14.76%. Cymbria Corp, Class A NAV: YTD: 18.07%; 1-year: 29.81%; 3-year: 7.51%; 5-year: 12.78%; 10-year: 17.47%; Since inception (Nov. 3, 2008): 15.16%. MSCI World Index: YTD: 12.40%; 1-year: 22.18%; 3-year: 12.38%; 5-year: 12.91%; 10-year: 14.90%; Since inception (Nov. 3, 2008): 11.96%.

Source: Morningstar Direct, Bloomberg LP. As at September 30, 2021. Cumulative total returns in C$. The MSCI World Index is a market-capitalization-weighted index comprising equity securities available in developed markets globally. We manage our Portfolios independently of the indexes we use as long-term performance comparisons. Differences including security holdings and geographic allocations may impact comparability and could result in periods when our performance differs materially from the index.

The graph shows how our focus on the long term, combined with our in-depth research, has delivered pleasing returns to unit holders and has helped them move closer to their Point B. You’ve given us an immense responsibility by entrusting your savings with us, and we are grateful for that. Thank you.

ii Source: Dalbar, Inc. 2020 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behaviour.

iii Source: The Motley Fool, “Tracking Fund Turnover”, Fool.com, November 10, 2016. https://www.fool.com/investing/mutual-funds/tracking-fund-turnover.aspx.

iv Source: Kinnel, Russel. “Do Managers Eat Their Own Cooking?” Morningstar Research Inc., 2008.

v Source: Chris Tidmore & Andrew Hon, “Patience with Active Performance Cyclicality: It’s Harder Than You Think”, The Journal of Investing 30, no. 4 (2021). Stat from State Street 2016 study.

vi Source: Kwoh, Leslie, “Investors Demand CEO Time”, WSJ.com, November 29, 2012. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324784404578145242728424164.

vii Source: Akre Capital, Bloomberg.

viii This amount varies by Investment team member and that other criteria besides salary applies. Additionally, there are additional criteria regarding Investment team members and their co-investment levels.

ix As at December 31, 2020.

x Source: CIBC Mellon. As at September 30, 2021. Total returns calculated in C$. Average since inception return of EdgePoint investor accounts with a minimum 10-year holding period. EdgePoint Portfolio returns are time-weighted to best reflect the manager’s performance based on compound growth rate, which isn’t impacted by portfolio cash flows. Money-weighted average investor return takes into account the investor’s decision(s) regarding the timing and magnitude of cash flows and represents their personal rate of return. Average EdgePoint investor since inception return excludes investor account transfers and switches. Series F is available to investors in a fee-based/advisory fee arrangement and doesn’t require EdgePoint to incur distribution costs in the form of trailing commissions to dealers.