Time is very precious in this life. While there’s time to play, time to work, time to enjoy, time to love, time to hate, time to read, time to think, time to spend, time to cry and time to waste, somehow there never seems to be enough time. And when it’s lost, it’s impossible to get back which is why time truly is precious. If you haven’t guessed already, this commentary is about time. It’s also about building wealth and how time is either on your side, or not. You’re often encouraged to seize the day, “carpe diem” and all that stuff because the clock is ticking. That applies to investing but in a different way. Investing isn’t so much about seizing the day but rather, mapping out your future and letting time do its thing. After reading this commentary you’ll have spent some time and we hope you’ll think it was time well spent because now you’ll appreciate that time is also money.

The book that fell into my lap

Twenty-four years ago I had the luxury of having some free time and given my relatively young age (as far as investing goes) I had time on my side. I read a Financial Times of Canada book entitled Investment Strategies – How to create your own & make it work for you. The book’s appendix had two tables showing how investment dollars could grow at various rates of return. Here’s a summary of some of the key numbers that caught my eye from the first table:

| Years | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% |

|---|

You can likely guess where my 21-year old eyes gravitated. My biggest challenge at the time was figuring out where I’d get the initial $1,000 investment! After that, all I needed to do was 20%/year for 40 years and when I was 61 I’d have $1.47 million. It would grow to over $3 million by the time I was 65. It didn’t seem right that I could get all that from a single $1,000 investment but it was worth a try.

I remember finding the next table even more mesmerizing. It shows that time can be your friend when it comes to investing. Time can also be your worst enemy but I’ll talk about that later.

| Years | 5% | 10% | 15% | 20% |

|---|

Investing is the act of forgoing consumption today for consumption at a later time. No matter what you call it, the nest egg, rainy day or retirement fund, it’s about saving now for later. This chart got me thinking – couldn’t I forgo $1,000 per year? What about $2,000 per year, or more? And what could I do with all the money saved by not spending that annual savings on a frivolous vacation or an expensive ski habit.

Let’s focus on the 10%/year column in the chart above. After five years, the investor has invested $5,000 and now has $6,716 for a gain of $1,716 or 35% on the $5,000 invested. Not bad, although for us five years is a very short time when it comes to investing (bet you don’t hear that from many people!). Seeing the modest compounding that occurred during these first five years is proof that it’s a short time. After 10 years (which is still a relatively short time in our business), the investor has $17,531 for a gain of $7,531 or 75% of the $10,000 invested. Again, not bad, but investing is hopefully a journey that lasts your lifetime, not a short 10-year interval. If you think about it, the reality is that 40 years is closer to most investors’ lifespan of investing. Even if you delay investing until you’re 40 years old, you’re probably planning to live at least another 40. By year 40 the investor has $486,852, yet only invested $40,000 over that timeframe for a profit of $446,852 or 11.2 times their investment! It just took time. Time we hopefully all have or time we’ve already been able to take advantage of.

Something getting in the way

Unfortunately most investors don’t experience the compounding outlined in the paragraph above which is too bad because it’s pretty simple math. Not only that, with long-term returns of stock indices being around 10%/year*, if investors simply owned a diversified basket of stocks and promptly forgot about them after the purchase, they would’ve gotten close to 10% per annum. So what gets in the way? We’d suggest that investors who haven’t experienced that kind of wealth generation have done something that caused them to have an investment process that’s inconsistent with their investment horizon.

Even if an investor is 60 years old, their investment horizon has to be at least 30 years – which may be counterintuitive to many investors. But if they’re lucky enough to live into their 90s, wouldn’t it be really silly to run out of money because they thought they’d die earlier? With a 30-year-plus investment horizon for a 60 year old, it becomes more apparent that being afraid of a little volatility seems ridiculous especially when we think about how long most investors’ time horizons really are. Taken one step further, measuring investment performance daily seems even sillier in this context, as does measuring the ups and downs of your monthly investment statements. It’s the short-term monitoring of your portfolios that ends up causing emotional stress that results in actions inconsistent with your long-term goals.

When you realize you have much longer than 10 years to invest, don’t a majority of investment styles like momentum investing or smart-beta gimmicks seem ridiculous? How about low-volatility funds, intelligent ETFs or fads due to trailing outperformance like emerging-market income, China related or diversified income? Understanding the tables above is paramount to coming to that realization. There’s no race, no sprint, just a very special, ultra-long marathon. All the less reason to try to figure out what will perform best next month or even next year. Those who do so are the investors who fail to experience the compounding shown above.

See Peter’s pain

About 10 years ago, I read another book that had a table that furthers our discussion of time. The book was called Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets, by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Here’s a summary of the table.

| Time Period | Probability |

|---|

The table shows the probability of making money over different periods assuming an investor has the tools to earn a 15% return in excess of Treasury bills with a 10% error rate (also known as volatility) in any given year. We’ll call this investor Peter. Peter obviously has some talents because this would mean that out of a 100 samples, 68 of them would fall within a band of a +5% to +25% return and 95 of those samples would be between -5% and +35% (for the statistics nerds out there, the author assumed a bell-shaped normal distribution).

Making time your enemy

Let’s assume nothing changes in Peter’s investment approach except he loads his portfolio into a performance monitoring app on his smartphone. Before this, while Peter regularly checked the fundamentals of his underlying investments to ensure they were sound, he only looked at his performance yearly. 93% of those years were positive and Peter was a great investor.

When looking at the table above, over a very narrow period, Peter suddenly appears talentless. If Peter is emotional like most other human beings, he feels the pain with every loss. By measuring performance over shorter timeframes, his time of pain is inadvertently increased at the expense of his time of pleasure. This is a bad trade-off because many studies have shown that the pain of loss is greater (by at least two times) than the joy of gain†.

It’s an even worse trade-off for Peter because these periods are just random noise and the normal variability of the portfolio and not the returns! To top it off, the variability is forever recurring. Peter is constantly required to go through those ups and downs to get to the returns he’s always experienced.

Peter initially started using his smartphone app to monitor his portfolio’s performance monthly. If you review the chart again, only 67% of those months are positive which means he would have four bad months in his first year. This starts to bother him because he’s used to having about one bad year out of 14 (93% of the years are positive). Halfway through the year he experiences a second month of losses and starts second-guessing himself. He starts working longer hours and begins monitoring his portfolio daily. Things keep getting worse because now 46% of days end with a loss which far outweighs his positive feelings on the up days that he now only experiences 54% of the time.

These constant shots of pain cause Peter a great deal of anxiety. Anxiety dramatically reduces his ability to handle situations without losing his cool or letting his emotions take over. Peter becomes more of an emotional wreck. His reaction to this pain is to deviate from a very successful approach that would allow for the type of compounding seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Continuous performance monitoring isn’t good for your mental health, but more importantly (for the purpose of this commentary of course!) it’s not good for your financial health. Peter was doing great before he started monitoring his results over short periods. Like many investors before him and likely many more to follow, he fell victim to his emotions. He didn’t even realize that he began monitoring the short-term variability of his portfolio, not its returns. Few do. And that’s how you can make time your enemy, when time is waiting to be your best friend.

Years versus days

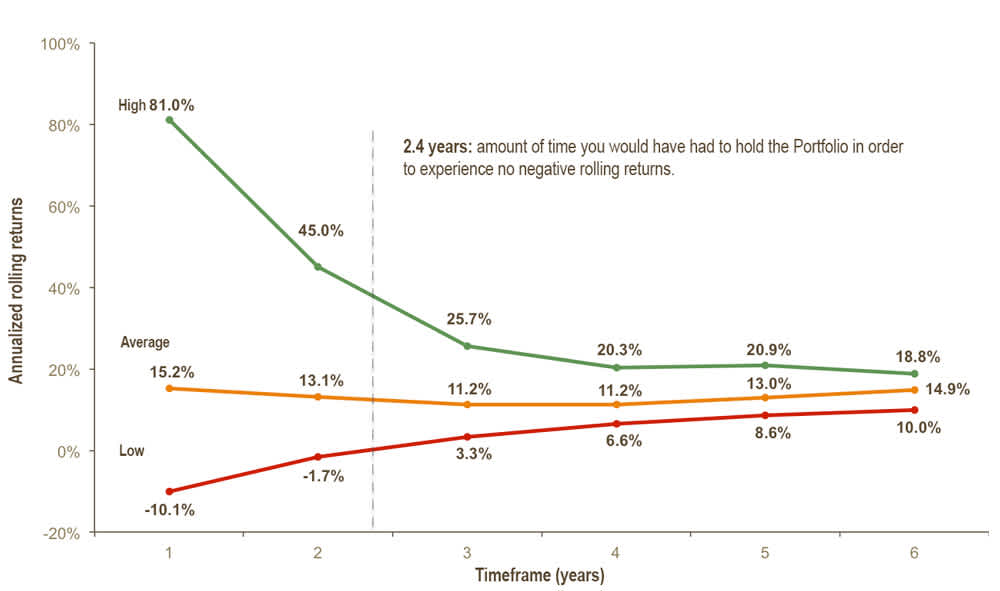

If you guessed that the variability of returns continues to diminish as we stretch out the period from days (from the chart above) to years, you’d be right. The chart below shows the best and worst rolling annual returns for EdgePoint Global Portfolio. Not an EdgePoint investor? Cymbria shares the same Investment team and by extension, the same investment approach. So these charts are examples of some of the portfolios your Investment team manages to further illustrate how the variability of returns diminishes with time. Of note, the worst 52-week experience for our investors since our inception was a loss of 8.9%††. The worst possible 2-year annual return was a loss of 3.4%. The worst 3-year return was a gain of 2.7%. If you’re like many of our partners and have been with us for at least six years, the worst six-year return was a positive 13.9%. Time really changes a lot of things! All those investors had to endure was the one-year period when the return was -8.9% to experience the reward of time. If you look at our EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio in the second chart, it also shows that the variability of returns moderates the longer you’ve invested with us.

EdgePoint Global Portfolio‡

Average rolling returns

Annualized returns as at September 30, 2015

EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series A: YTD: 7.99%; 1-year: 17.93%; 3-year: 24.36%; 5-year: 17.07%; since inception: 17.71%.

EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio§

Average rolling returns

Annualized returns as at September 30, 2015

EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio, Series A: YTD: -1.17%; 1-year: -0.21%; 3-year: 11.89%; 5-year: 8.25%; since inception: 14.37%.

Whereas looking at monthly statements seemed silly for Peter, looking at any given one-year timeframe can be just as damaging. If you give time a chance, it will almost certainly prove itself to be a generous friend because time really is money.

†Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, October 1992, Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman.

††Series A performance, 11/17/2008 – 08/31/2015.

‡EdgePoint Global Portfolio, Series A. Date range: 11/17/2008 – 08/31/2015.

§EdgePoint Canadian Portfolio, Series A. Date range: 11/17/2008 – 08/31/2015.